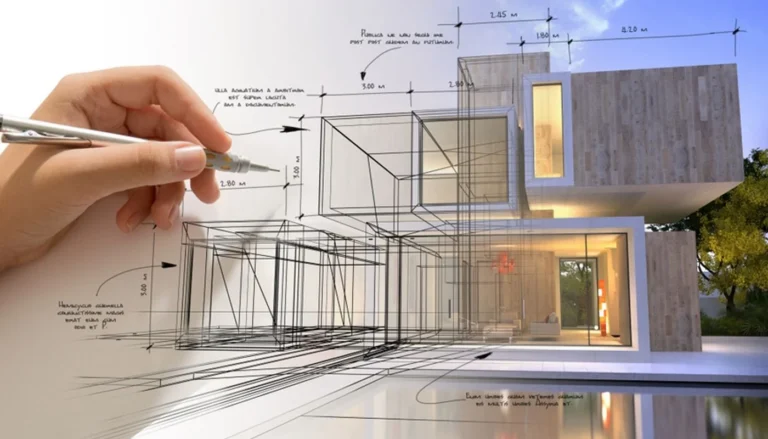

Finding the Right Home Architect Near Me: A Definitive Guide to Residential Design

The realization of a bespoke residential environment is an intricate exercise in balancing personal aspiration with the uncompromising realities of physics, regulation, and local ecology. For many property owners, the transition from an abstract desire for “space” to a physical, habitable structure requires a specialized intermediary capable of navigating a labyrinth of technical and aesthetic variables. This is not merely an aesthetic endeavor; home architect near me, it is a structural and legal mandate that dictates how a home will function, age, and retain value over decades.

The search for local expertise is often driven by the necessity of “contextual intelligence.” While architectural principles—such as proportion, light, and massing—are universal, their application is hyper-local. A structure must contend with specific soil compositions, microclimates, and municipal zoning ordinances that vary significantly from one jurisdiction to the next. Consequently, the relationship between a homeowner and their architect is less about “buying a plan” and more about engaging a guide who understands the specific geological and political landscape of the region.

Modern residential architecture has moved beyond the era of simple drafting. It now encompasses sophisticated energy modeling, material lifecycle analysis, and complex project management. As sustainability mandates and building codes become increasingly stringent, the margin for error in residential design has narrowed. The architect’s role has expanded to encompass that of a lead strategist, ensuring that every square foot of the build is optimized for performance while adhering to the cultural and historical vernacular of the surrounding neighborhood.

Understanding “home architect near me”

When a homeowner initiates a search for a home architect near me, they are frequently seeking a solution to a “multi-variable optimization problem.” The query itself is often a proxy for several underlying needs: technical feasibility, regulatory navigation, and aesthetic translation. One of the primary misunderstandings in this field is the conflation of an architect with a “house designer” or a “draftsperson.” While all may produce floor plans, an architect is a licensed professional whose training encompasses structural integrity, life safety, and the legal responsibility for the building’s performance.

The “local” component of this search is critical because architecture is, by definition, site-specific. A professional located in the same geographic region possesses an inherent understanding of the local “Permitting Path.” They are familiar with the specific personalities of local building departments, the quirks of regional environmental protections (such as wetlands or seismic zones), and the availability of local craftspeople capable of executing specific details. An architect from a different climate zone might specify a “flat roof” assembly that works in the high deserts of Arizona but would be a catastrophic failure in the heavy snow loads of Vermont.

Oversimplification risks in this sector are high. Property owners often view the architect as a “cost center”—an expense to be minimized—rather than a “value generator.” This perspective ignores the fact that a well-designed home can reduce lifetime energy costs by 40% and significantly increase resale premiums. The “design” is not just the facade; it is the logic of how air moves through the house, how natural light reduces the need for electricity, and how the internal layout adapts to the changing needs of a family over twenty years.

Historical and Systemic Evolution of Residential Practice

Residential architecture was historically a matter of vernacular tradition—building with what was available within a twenty-mile radius. In the early 20th century, the “Architect” was often a luxury reserved for the upper echelons of society, while the middle class relied on pattern books and local builders. However, as the complexity of home systems (plumbing, electrical, HVAC) increased, the need for centralized coordination became paramount.

The post-war era saw a move toward “industrialized housing,” where standardized plans were replicated across vast suburbs. This era prioritized speed and cost over site-specific design. The modern era represents a “Neo-Vernacular” shift. Today, the profession is moving back toward site-specificity but is doing so through the lens of high-technology. We are seeing a return to local materials—stone, timber, and earth—but engineered through 3D modeling and precision manufacturing to achieve performance levels that were previously impossible.

Conceptual Frameworks and Mental Models in Design

To bridge the gap between a client’s vision and a physical structure, architects employ specific mental models that prioritize functional longevity.

-

The “Six Layers” Framework: This model, popularized by Stewart Brand, views a house as a series of nested systems with different lifespans: Site (eternal), Structure (30–300 years), Skin (20 years), Services (7–15 years), Space Plan (3–10 years), and Stuff (daily). A local architect ensures that changes to the “Space Plan” don’t require expensive modifications to the “Structure.”

-

Prospect and Refuge: This is a psychological model used to create comfort. A home should provide “refuge” (a sense of enclosure and safety) and “prospect” (a clear view of the surrounding environment). Balancing these two allows a home to feel both cozy and expansive.

-

The Thermal Envelope Logic: This framework treats the house as a biological skin. In a local context, the architect must decide whether the house should be “breathable” or “hermetically sealed,” depending on the humidity and temperature swings of the region.

Categories of Architectural Services and Strategic Trade-offs

| Service Level | Primary Focus | Trade-off |

| Consultation Only | Feasibility and “Broad-Strokes” ideas | Low cost, but no follow-through on technical execution. |

| Basic Permit Sets | Minimum documentation required by law | Functional and legal, but lacks interior detail and craft. |

| Full Architectural Services | Design, bidding, and construction oversight | High initial investment, but ensures the highest build quality. |

| Design-Build Integration | Seamless design and construction via one firm | Maximum efficiency, but the homeowner loses the “check and balance” of an independent architect. |

Decision Logic

Choosing between these categories depends on the “Risk Tolerance” of the owner. For a simple garage conversion, a permit set may suffice. For a custom “forever home,” full services are generally the only way to ensure that the vision on paper is not diluted by the shortcuts often taken on a construction site.

Real-World Scenarios: From Urban Infill to Rural Estates home architect near me

Scenario 1: The Tight Urban Infill

-

The Context: A 25-foot wide lot between two existing structures in an older city.

-

Architect’s Value: Navigating “easements” and “party wall” agreements while maximizing vertical light via light wells or clerestory windows.

-

Failure Mode: A non-professional might design a home that meets the square footage requirements but feels like a dark “tunnel” because they didn’t account for the sun’s path between the tall neighbors.

Scenario 2: The Wildfire-Prone Hillside

-

The Context: A scenic lot in a region with high “WUI” (Wildland-Urban Interface) risk.

-

Architect’s Value: Selecting non-combustible materials (metal, concrete, specialized glass) and designing “defensible space” that meets fire codes without looking like a bunker.

-

Second-Order Effect: These material choices often lower the homeowner’s insurance premiums, providing a direct ROI on the design fee.

Scenario 3: The Multi-Generational “ADU”

-

The Context: Adding an Accessory Dwelling Unit in a backyard for aging parents.

-

Architect’s Value: Designing for “Universal Access” (no-step entries, wider halls) that integrates aesthetically with the main house.

Economic Dynamics: Direct Costs and Resource Allocation

Architectural fees are typically structured as a percentage of construction costs (8–15%), a flat fee, or an hourly rate.

Typical Resource Allocation for a $1M Custom Build

| Phase | Percentage of Fee | Outcome |

| Schematic Design | 15% | The “Concept” and floor plans. |

| Design Development | 20% | Material selection and system integration. |

| Construction Docs | 40% | The “Instruction Manual” for the builder. |

| Bidding/Negotiation | 5% | Selecting the right contractor for the right price. |

| Construction Admin | 20% | Ensuring the builder follows the plans exactly. |

The opportunity cost of hiring the wrong professional is often invisible until Year 5 of homeownership. Poorly designed drainage might lead to a $50,000 foundation repair, or a lack of proper solar shading might lead to $400 monthly electricity bills that could have been $100.

Tools, Strategies, and Support Systems home architect near me

A modern architect’s office is a high-tech laboratory.

-

BIM (Building Information Modeling): 3D software that identifies “clashes” (e.g., a plumbing pipe trying to go through a steel beam) before construction starts.

-

Energy Simulation: Tools that predict exactly how much energy the house will use based on local weather data.

-

VR Walkthroughs: Allowing the client to “stand” in their kitchen before a single nail is driven.

-

Site LiDAR: Laser scanning of the lot to ensure the house sits perfectly on the topography.

-

Material Libraries: Physical and digital databases of local stone, timber, and sustainable composites.

Risk Landscape and Failure Modes home architect near me

-

Regulatory Risk: Designing a home that the local “Planning Board” rejects because it violates a minor “setback” or “height” restriction.

-

Scope Creep: Adding features during design that push the project beyond the homeowner’s financial capacity.

-

Communication Breakdown: The architect creates a masterpiece that the homeowner finds “unlivable” because the architect didn’t listen to how the family actually uses their mudroom.

-

Technical Failure: Specifying a new “experimental” material that hasn’t been tested in the local climate, leading to water intrusion.

Governance, Maintenance, and Long-Term Adaptation

A house is a “performing asset.” It requires a governance plan.

Maintenance Cycles

-

Annual: Inspecting the “Skin” (caulking, paint) to ensure the structure remains dry.

-

Decadal: Reviewing the “Services” (HVAC, Water Heater) for efficiency upgrades.

-

Generational: Evaluating the “Space Plan” as children move out or parents move in.

Trigger Points: If a homeowner notices condensation on the inside of windows or “hot spots” on the second floor, these are triggers to bring the architect back for a “Performance Audit.”

Measurement, Tracking, and Evaluation

How do you evaluate the “success” of a residential architect?

-

Quantitative: Comparing the “Estimated Energy Use” in the design phase to the “Actual Utility Bills” after one year of occupancy.

-

Resale Value: How does the home’s value appreciate compared to “Builder Grade” homes in the same zip code?

-

Qualitative: “The 5-Senses Test.” Is the home quiet? Is the light pleasant? Does the air feel fresh?

-

Documentation: Does the homeowner possess a “Digital Twin” or a complete “As-Built” set of drawings for future repairs?

Common Misconceptions and Industry Myths

-

“Architects are only for expensive houses.” In reality, small houses need architects more because there is less room for error. Every square inch must work twice as hard.

-

“I can just use a contractor’s draftsperson.” This removes the “checks and balances.” An independent architect works for the homeowner, not the builder, and ensures the builder doesn’t cut corners.

-

“Modern houses are cold and impersonal.” Modernism is a tool for light and efficiency; it can be as “warm” as any cottage depending on the material palette.

-

“The builder knows more about building.” A builder knows how to assemble; an architect knows why the assembly works. Both are necessary.

Conclusion

The decision to hire a home architect near me is fundamentally an act of stewardship. It is the recognition that a home is more than a shelter; it is a complex machine and a long-term financial instrument. By engaging a professional who understands the local context, the homeowner ensures that their residence is not just a reflection of their current taste, but a resilient, efficient, and valuable asset that will endure for generations. True architectural success is found where the beauty of a design is perfectly matched by its technical performance and its harmony with the local landscape.