The Virtual Architect: A Definitive Guide to Digital Building Design

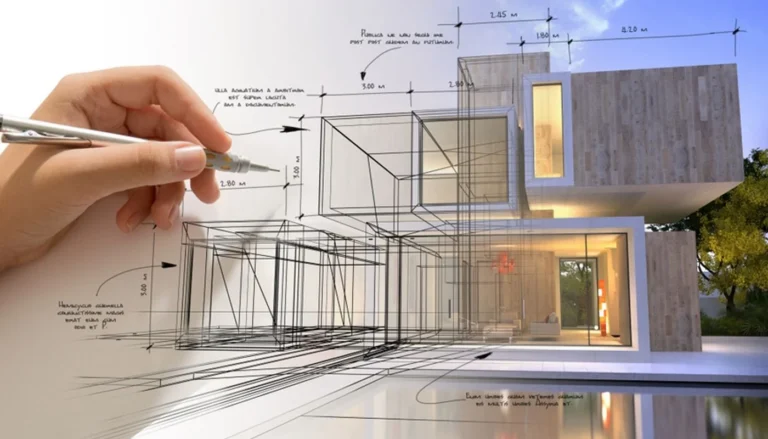

The traditional image of the architect hunched over a drafting table has long since evaporated, replaced by a landscape of immersive data environments and algorithmic precision. In this contemporary era, the demarcation between physical structure and digital simulation is no longer a clear line but a gradient. This shift has given rise to a specialized professional identity—one that operates at the intersection of spatial theory, software engineering, and project management. This role, virtual architect, often operating remotely or within distributed teams, redefines the delivery of the built environment through high-fidelity digital twins and predictive modeling.

As urbanization accelerates and the demand for resource-efficient housing grows, the reliance on remote architectural services and automated design workflows has moved from the periphery to the core of the industry. This is not merely about using computers to draw; it is about utilizing the computer to think through the complexities of building codes, material performance, and occupant behavior before a single ounce of concrete is poured. The democratization of high-performance hardware and cloud-based collaboration tools has allowed for a globalized exchange of architectural expertise, decoupling the design process from geographical constraints.

However, the transition to a fully digitized architectural workflow introduces profound structural challenges. It requires a fundamental rethinking of liability, intellectual property, and the nature of professional mentorship. When the primary deliverable is a data-rich model rather than a set of static blueprints, the relationship between the designer, the contractor, and the client undergoes a radical transformation. Understanding this evolution is essential for anyone navigating the current landscape of residential or commercial development, as the digital decisions made in the early phases of a project now carry more weight than ever before.

Virtual Architect

To define the role of a virtual architect, one must look beyond the literal interpretation of “remote designer.” In a professional and industrial sense, it describes a practitioner who utilizes a digital-first methodology to orchestrate the entire lifecycle of a building. This involves the creation of a “Digital Twin”—a virtual replica of a physical building that contains not just its geometry, but its plumbing, electrical loads, and thermal properties. This professional serves as a bridge between abstract architectural intent and the precise data requirements of modern robotic fabrication and supply chain management.

Common misunderstandings often equate this role with 3D rendering or simple CAD drafting. While visualization is a component, the core value lies in “information architecture.” A sophisticated digital design does not just look like a house; it behaves like one. It can simulate how a shadow will move across a room on the winter solstice or how the air pressure will change during a storm. The risk of oversimplification is high here: if a client views the digital process as merely “drawing,” they often fail to invest in the data-cleansing and clash-detection phases that are critical for avoiding expensive on-site errors.

Furthermore, the “virtual” aspect refers to the decoupling of the professional from the site. This allows for a hyper-specialized approach where a designer in Scandinavia might optimize the thermal envelope for a project in Canada, while a lighting specialist in Japan calibrates the circadian rhythm of the interior. This distributed expertise is only possible through the rigorous application of shared digital protocols, turning the act of design into a globalized, data-driven collaborative effort.

Historical and Systemic Evolution

The trajectory toward digital architecture began with the advent of Computer-Aided Design (CAD) in the 1960s and 70s, which initially aimed to replicate the drafting table digitally. However, the true systemic shift occurred with the transition to Building Information Modeling (BIM). BIM replaced lines and circles with “smart objects”—a digital wall “knows” its R-value, its cost per square foot, and its structural load capacity. This was the moment the architect shifted from a composer of images to a manager of databases.

In the early 2000s, the rise of parametric design allowed architects to input variables—such as sunlight, wind, or budget—and let algorithms generate optimal forms. This moved the profession away from static “style” toward dynamic “performance.” Today, we are in the era of the Metaverse and the Digital Twin. The home is now modeled not just for construction, but for lifelong operation. Sensors in the physical building feed data back to the virtual model, allowing the architect to monitor the “health” of the building remotely. The evolution is clear: from representation to simulation to real-time synchronization.

Conceptual Frameworks and Mental Models

To master the nuances of virtual architecture, practitioners and clients must adopt specific mental models that differ from traditional construction logic.

-

The Single Source of Truth (SSOT): This model dictates that there is only one authoritative digital model. Any change made by the structural engineer must be instantly reflected in the architect’s model. This eliminates the “version control” issues that historically led to site errors.

-

The “Clash Detection” Framework: This treats the virtual environment as a testing ground where the plumbing is “clashed” against the structural beams digitally. Every clash resolved in the computer saves thousands of dollars in the field.

-

The Lifecycle Data Continuum: This framework views the architectural model as a living document. It is used for design, then for construction (sending data to CNC machines), then for facility management, and eventually for deconstruction and recycling.

-

The Performance-First Design Loop: Instead of starting with a shape, the designer starts with a performance goal (e.g., net-zero energy). The virtual environment then iteratively tests different shapes until the goal is met.

Key Categories and Architectural Variations virtual architect

The application of digital architectural expertise varies significantly depending on the project’s scale and the level of technological integration required.

| Category | Primary Focus | Key Trade-off |

| BIM-Centric Design | Data-rich modeling for complex builds | High upfront software and labor costs |

| Generative/Parametric | Algorithmic optimization of form | Risk of creating “unbuildable” geometry |

| Virtual Reality (VR) Immersive | Occupant experience and spatial flow | Hardware intensive; can ignore technical specs |

| Prefab/Modular Integration | Direct-to-fabrication data links | Limits on-site customization |

| Digital Twin Operation | Long-term maintenance and monitoring | Requires ongoing data subscription and sensors |

| Remote Consultation | Globalized design expertise | Lack of physical “site-feel” and context |

Decision Logic: Selecting the right category depends on the project’s “Technical Density.” A simple renovation may only require remote consultation, whereas a high-performance, net-zero modular home requires deep BIM and prefab integration to succeed.

Detailed Real-World Scenarios virtual architect

Scenario 1: Resolving a Multidisciplinary Structural Conflict

A residential project features a complex, cantilevered living room.

-

Constraint: The mechanical ducting must pass through a structural steel beam.

-

Decision Point: The designer uses 3D clash detection to move the ducting in the virtual model before the beam is fabricated.

-

Failure Mode: If the ducting was moved on-site, the structural integrity of the beam could be compromised by unauthorized drilling.

-

Second-Order Effect: The contractor gains confidence in the digital model, leading to tighter bids and less “contingency” padding in the budget.

Scenario 2: Remote Solar Optimization for a Passive House

An architect in London is designing a home for a client in a high-altitude desert.

-

Constraint: Extreme temperature swings and high UV exposure.

-

Decision Point: Utilizing a “virtual architect” approach, the designer runs 365-day solar simulations to determine the exact depth of roof overhangs.

-

Outcome: The home achieves 40% less heat gain than its neighbors without increasing the cooling budget.

Planning, Cost, and Resource Dynamics

The financial model of digital-first architecture is heavily front-loaded. Traditional architecture often delays detailed decisions until the construction phase, leading to “Change Orders.” Virtual architecture invests heavily in the “Pre-Design” and “Modeling” phases to eliminate these surprises.

Cost Variance: Traditional vs. Virtual Workflow

| Phase | Traditional (% of Budget) | Virtual (% of Budget) | Payback |

| Pre-Design/Simulation | 5% | 15% | High (Reduces Field Errors) |

| Detailed Modeling/BIM | 10% | 25% | Very High (Clash Detection) |

| On-Site Supervision | 15% | 5% | Neutral (Model is the Guide) |

| Construction Change Orders | 10–20% | 1–3% | Direct Savings |

Tools, Strategies, and Support Systems

-

Revit / ArchiCAD: The foundational BIM software platforms that allow for “smart object” modeling.

-

Grasshopper / Dynamo: Visual programming tools used for generative and parametric design.

-

Point Cloud Scanning (LiDAR): A tool for “importing” the physical site into the virtual model with millimeter precision.

-

Enscape / Twinmotion: Real-time rendering tools that allow clients to “walk through” the home in VR.

-

Common Data Environments (CDE): Cloud platforms like Procore or Autodesk Construction Cloud that ensure everyone is working on the latest version of the file.

-

Environmental Analysis Engines: Tools like Ladybug or Honeybee that simulate light, wind, and energy.

Risk Landscape and Failure Modes virtual architect

The “Digital Fragility” of virtual architecture presents a unique set of risks that must be managed.

-

The “Garbage In, Garbage Out” Risk: If the initial site survey (the data foundation) is inaccurate, the entire virtual model becomes a sophisticated lie.

-

Interoperability Failures: When the structural engineer’s software doesn’t “talk” to the architect’s software, data is lost in translation, leading to site errors.

-

Cybersecurity and IP Theft: Digital models are high-value assets. If a server is breached, the entire architectural IP of a project can be stolen or held for ransom.

-

Compounding Errors: A small error in a parametric script can be replicated thousands of times across a model, leading to systemic structural weaknesses.

Governance, Maintenance, and Long-Term Adaptation virtual architect

A digital architectural asset requires ongoing governance to remain useful throughout the building’s life.

-

Model Audit Cycles: Every project milestone should trigger a “Model Integrity Check” to ensure that data entry standards are being met.

-

Handover Protocols: The transition from the architect to the facility manager is the most dangerous moment for data. A clear “Digital Asset Handover” document is required.

-

Software Versioning: As software updates, old models can become unreadable. A strategy for “archival” vs. “active” models is essential.

Layered Digital Maintenance Checklist:

-

Weekly: Synchronization of multidisciplinary models.

-

Monthly: Conflict report and resolution log.

-

Post-Construction: As-built model verification via LiDAR scan.

Measurement, Tracking, and Evaluation

-

Leading Indicators: Number of clashes resolved per month in the model; simulation accuracy (predicted vs. simulated performance).

-

Lagging Indicators: Number of Requests for Information (RFIs) from the job site; total cost of change orders.

-

Qualitative Signals: Client’s spatial understanding during VR walk-throughs; ease of facility management using the digital twin.

Common Misconceptions and Oversimplifications

-

Myth: It’s just a 3D model. Correction: It is a database of material science, cost, and physics that happens to have a 3D interface.

-

Myth: Remote architects can’t understand the site. Correction: Through LiDAR scanning, drone surveys, and satellite data, a remote designer often has more accurate site data than a local architect with a tape measure.

-

Myth: It’s only for large buildings. Correction: The precision of digital design is actually more impactful for small homes where every square inch and dollar counts.

-

Myth: It’s more expensive. Correction: The design fee is higher, but the Total Project Cost is almost always lower due to the elimination of field waste.

Ethical and Practical Considerations

The rise of the digital architectural professional raises questions about the “humanity” of design. As algorithms begin to suggest the “best” room layout, we must ask what is lost in terms of cultural nuance and poetic space. Practically, the globalized nature of virtual architecture can bypass local expertise. There is an ethical imperative to ensure that digital precision is informed by local ecological knowledge and community needs.

Conclusion: The Synthesis of Data and Habitation

The transition to a digital-first architectural methodology is an irreversible evolution in how we conceive and construct our world. By embracing the complexity of simulation, the modern architect can deliver structures that are more efficient, more resilient, and more attuned to the needs of their occupants than ever before. However, this power comes with a new responsibility: the mastery of data. The buildings of the future will be built twice—once in the infinite space of the computer, and once in the physical reality of the site. Success lies in ensuring that the two are in perfect harmony.